This exhibit was developed by Glanmore National Historic Site in partnership with the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County and the John M. Parrott Gallery for the Quinte Arts Festival (2025). It explores Susanna Moodie's life in Belleville through her own words. It was originally on display at the John M. Parrott Gallery and included supplementary pieces and interactive elements to complement the interpretation. The original panels with images and text can be viewed below, thank you for visiting!

Life In The Clearings: Susanna Moodie's Belleville

Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) lived in Belleville for over forty years, following seven years in the harsh Canadian wilderness. Her love for Belleville shines through in her autobiographical work Life in the Clearings versus the Bush (1853).

Her writings capture the realities of pioneer life in Canada, and her vivid storytelling helped shape Canadian literature, cementing her legacy as a prominent voice of the early settler experience. This exhibit explores Susanna Moodie’s Belleville through her writings which are supported by historic archival material, images, artwork, and maps.

Who was Susanna Moodie?

Born Susanna Strickland in 1803, near Bungay, England, she was the sixth daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Strickland. She was raised at Reydon Hall, a country manor house, on the outskirts of the village of Reydon in the county of Suffolk in England. Susanna and her siblings were artistic, excelling in visual and literary arts from a young age.

In 1831, she married John Wedderburn Dunbar Moodie, a Scottish born British Army officer and writer himself. In 1832, the Moodies and their young daughter immigrated to Upper Canada. They first settled in Port Hope, before moving to the shore of Lake Katchawanook (near present day Lakefield) to take up J.W.D. Moodie’s land grant he received for military services. The move also brought them closer to Susanna’s sister Catharine and her husband Thomas Parr-Trail, and brother Samuel Strickland.

Susanna often wrote to earn extra money. In her early years in Belleville, she wrote a memoir about living in the the untamed Canadian wilderness, and the struggles she encountered there. Roughing it in the Bush was published in 1852, and was widely popular with those interested in learning about the British settler experience in Canada. Her second memoir, Life in the Clearings versus the Bush, was published in 1853 and was also a success. She also published novels, children’s books, articles, and poetry throughout her lifetime.

The Moodies moved to Belleville in 1840 when J.W.D. Moodie was appointed Sheriff of Hastings County. He died in Belleville in 1869. Susanna Moodie died in Toronto in 1885 at the age of 81. They are both interred in the Belleville Cemetery

Photographs include a close-up photograph of Susanna Moodie, a map of Suffolk, England and a photograph of the manor house Reydon Hall where Moodie grew up, and a photograph of Moodie seated on the front porch of her Belleville home with her husband standing beside her, surrounded by friends or family.

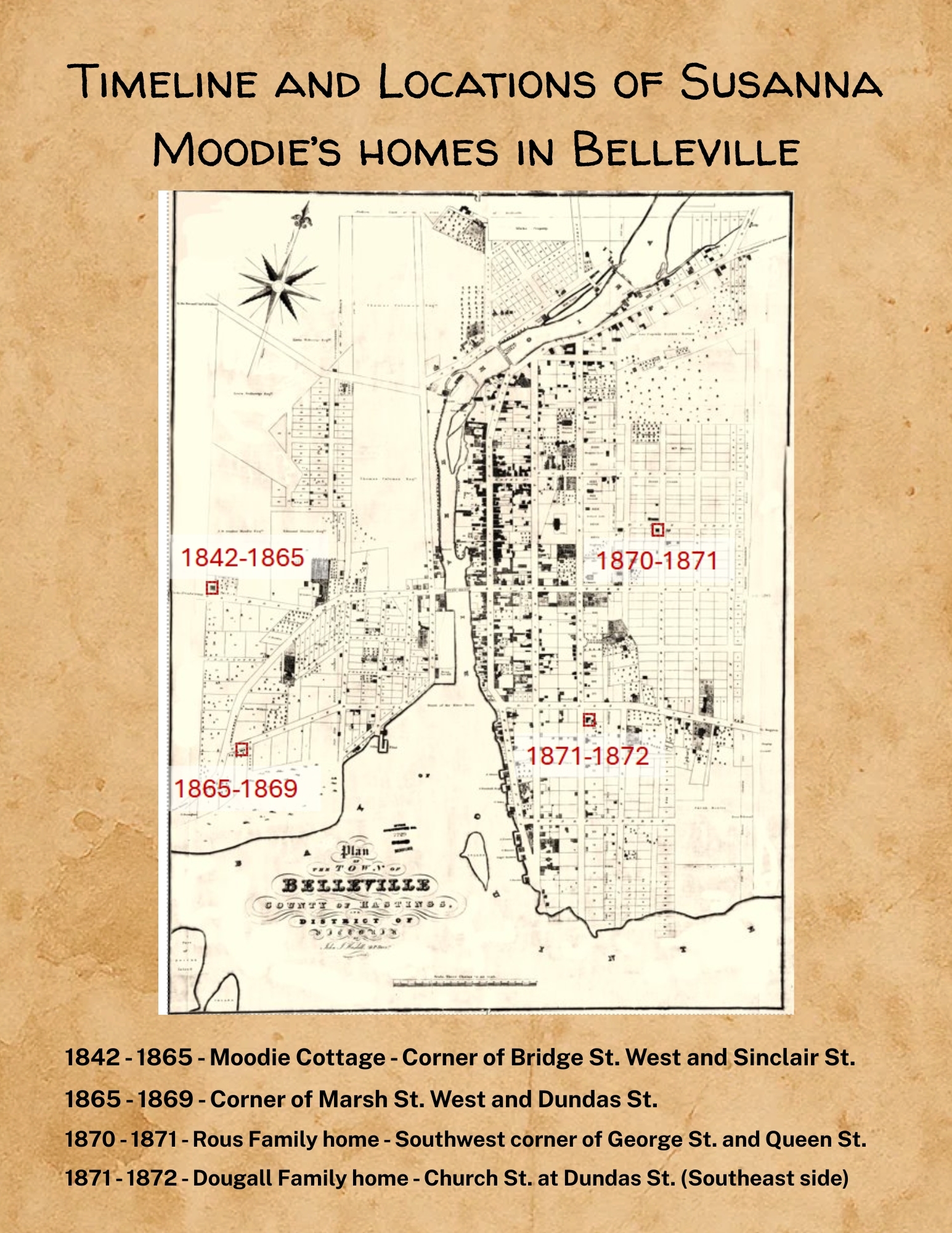

Mapping The Moodies

"The town of Belleville, in 1840, contained a population of 1,500 souls, or thereabouts. The few street it then possessed were chiefly composed of frame houses, put up in the most unartistic and irregular fashion, their gable ends or fronts turned to the street, as it suited the whim or convenience of the owner without the least regard to taste or neatness. At that period there were only two stone houses and two of brick in the place. On of these wonders of the village was the court-house and gaol; the other three were stores. The dwellings of the wealthier portion of the community were distinguished by a coat of white or yellow paint, with green or brown doors and window blinds; while the houses of the poorer class retained the dull grey which the plain boards always assume after a sort exposure to the weather."

- From Chapter II, Sketches of Society, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

The Moodie’s first home in Belleville was destroyed by a fire in December 1840. They bought a stone cottage on Bridge Street for £300 ($80,000 in today’s money) from Hannah Cowper in 1842 and lived there for the next 24 years. In 1866, Susanna and her husband moved into a small cottage near the bay-shore on Marsh Street with their servant, Margaret, described by Susanna in 1868 as “a good and faithful woman though Irish and a Catholic…and whom I regard as a tried and valued friend.”

“…I rise at six, read a chapter to the children, with short appropriate prayers. Get breakfast ready with the help of one servant, all I can afford to keep… Make bread, or pies as required. Give orders for dinner and sit down to write.”

Susanna’s life at Moodie Cottage on Bridge St., from a letter to her publisher, Richard Bentley (30 Dec 1853)

In a letter to her friend, Allen, Ransome (26 Dec 1868) she described the Marsh St. cottage as “…a little cottage with just room enough to hold us, but beautifully situated on the edge of our lovely bay…”

After John Moodie’s death, Susanna left the Marsh Street cottage to stay with family for a while, before returning to Belleville to lodge with Frederick Rous and his family at 17 Queen Street. In a letter to her sister Catherine Parr Traill (dated 18 Nov 1870), she wrote of the Rous home, “I have a large, nicely furnished bedroom with a stove in it, and carpeted floor and everything comfortable and handy. I can remain in my own room or join the family when I like, and then, I am independent. My own absolute mistress, and to me this is life...I am near to the dear husband. A couple of minutes walk brings me to his grave, and every fine day, I go alone and spend some time in communion with the dear spirit, who seems to meet me on that spot.”

In March 1871 the Rous family left Belleville for Colorado, and Susanna took up lodgings with Elizabeth Dougall and her daughter, Hester, until the summer of 1872. After this, Susanna lived with family members in Lakefield and Toronto until her death on April 8th, 1885. In a letter to her daughter, Katie Vickers (2 Jun 1872), she described her time at the Dougall residence as a home of, “miserable and begrudged scarcity and eternal liver and fish dinners…I am so glad I got away from that stern old woman…”

Photographs include an image of Moodie and her husband with their daughter-in-law on the front porch of their cottage on Bridge St., and a later photo of the exterior of the cottage from ca. 1920.

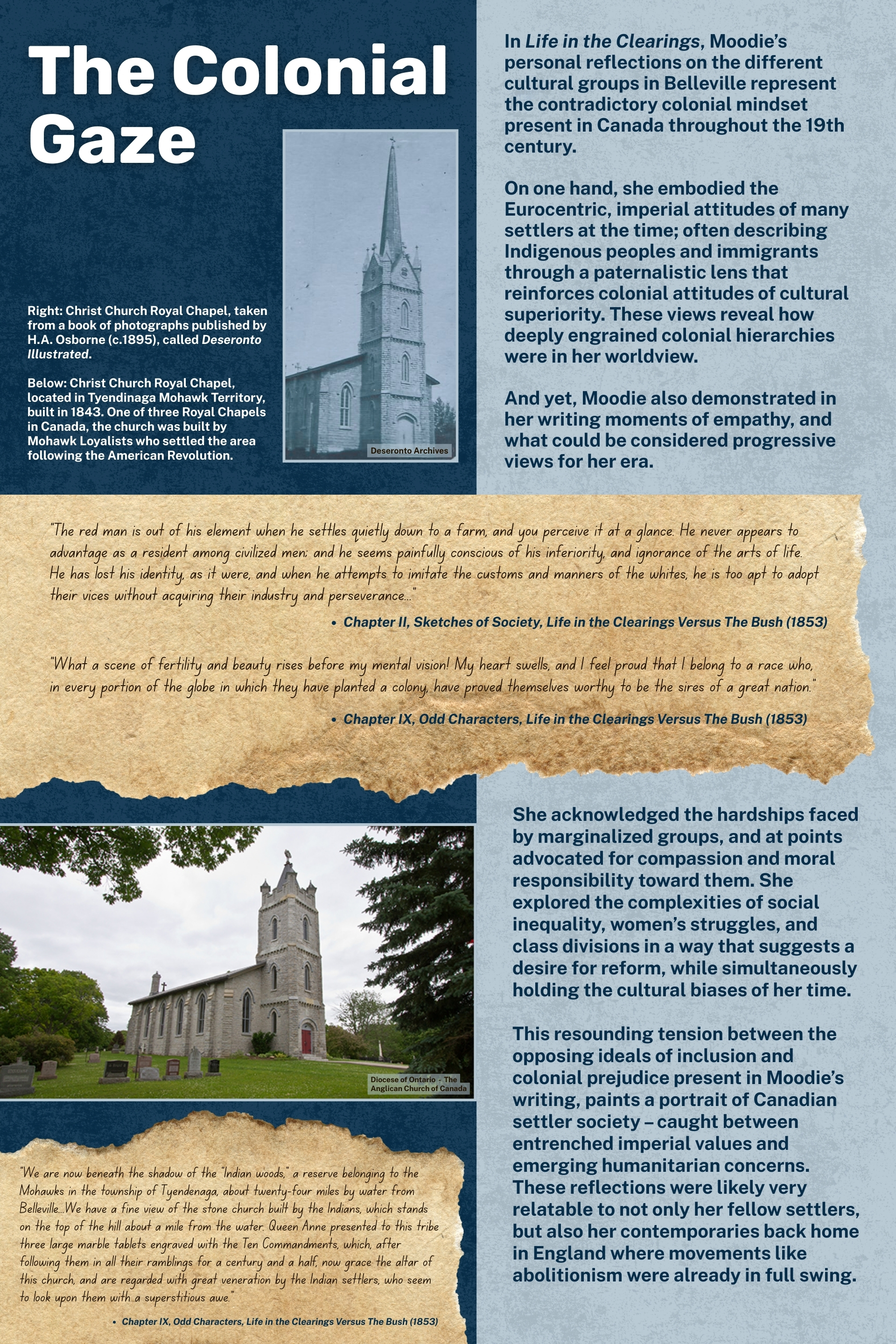

The Colonial Gaze

In Life in the Clearings, Moodie’s personal reflections on the different cultural groups in Belleville represent the contradictory colonial mindset present in Canada throughout the 19th century.

On one hand, she embodied the Eurocentric, imperial attitudes of many settlers at the time; often describing Indigenous peoples and immigrants through a paternalistic lens that reinforces colonial attitudes of cultural superiority. These views reveal how deeply engrained colonial hierarchies were in her worldview.

“The red man is out of his element when he settles quietly down to a farm, and you perceive it at a glance. He never appears to advantage as a resident among civilized men; and he seems painfully conscious of his inferiority, and ignorance of the arts of life. He has lost his identity, as it were, and when he attempts to imitate the customs and manners of the whites, he is too apt to adopt their vices without acquiring their industry and perseverance...”

- From Chapter II, Sketches of Society, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

And yet, Moodie also demonstrated in her writing moments of empathy, and what could be considered progressive views for her era.

She acknowledged the hardships faced by marginalized groups, and at points advocated for compassion and moral responsibility toward them. She explored the complexities of social inequality, women’s struggles, and class divisions in a way that suggests a desire for reform, while simultaneously holding the cultural biases of her time.

"What a scene of fertility and beauty rises before my mental vision! My heart swells, and I feel proud that I belong to a race who, in every portion of the globe in which they have planted a colony, have proved themselves worthy to be the sires of a great nation.”

- From Chapter IX, Odd Characters, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

This resounding tension between the opposing ideals of inclusion and colonial prejudice present in Moodie’s writing, paints a portrait of Canadian settler society – caught between entrenched imperial values and emerging humanitarian concerns. These reflections were likely very relatable to not only her fellow settlers, but also her contemporaries back home in England where movements like abolitionism were already in full swing.

“We are now beneath the shadow of the "Indian woods," a reserve belonging to the Mohawks in the township of Tyendenaga, about twenty-four miles by water from Belleville...We have a fine view of the stone church built by the Indians, which stands on the top of the hill about a mile from the water. Queen Anne presented to this tribe three large marble tablets engraved with the Ten Commandments, which, after following them in all their ramblings for a century and a half, now grace the altar of this church, and are regarded with great veneration by the Indian settlers, who seem to look upon them with a superstitious awe.”

- From Chapter IX, Odd Characters, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

Photographs include Christ Church Royal Chapel, taken from a book of photographs published by H.A. Osborne (c.1895), called Deseronto Illustrated; and Christ Church Royal Chapel (ca. 2020), located in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, built in 1843. One of three Royal Chapels in Canada, the church was built by Mohawk Loyalists who settled the area following the American Revolution.

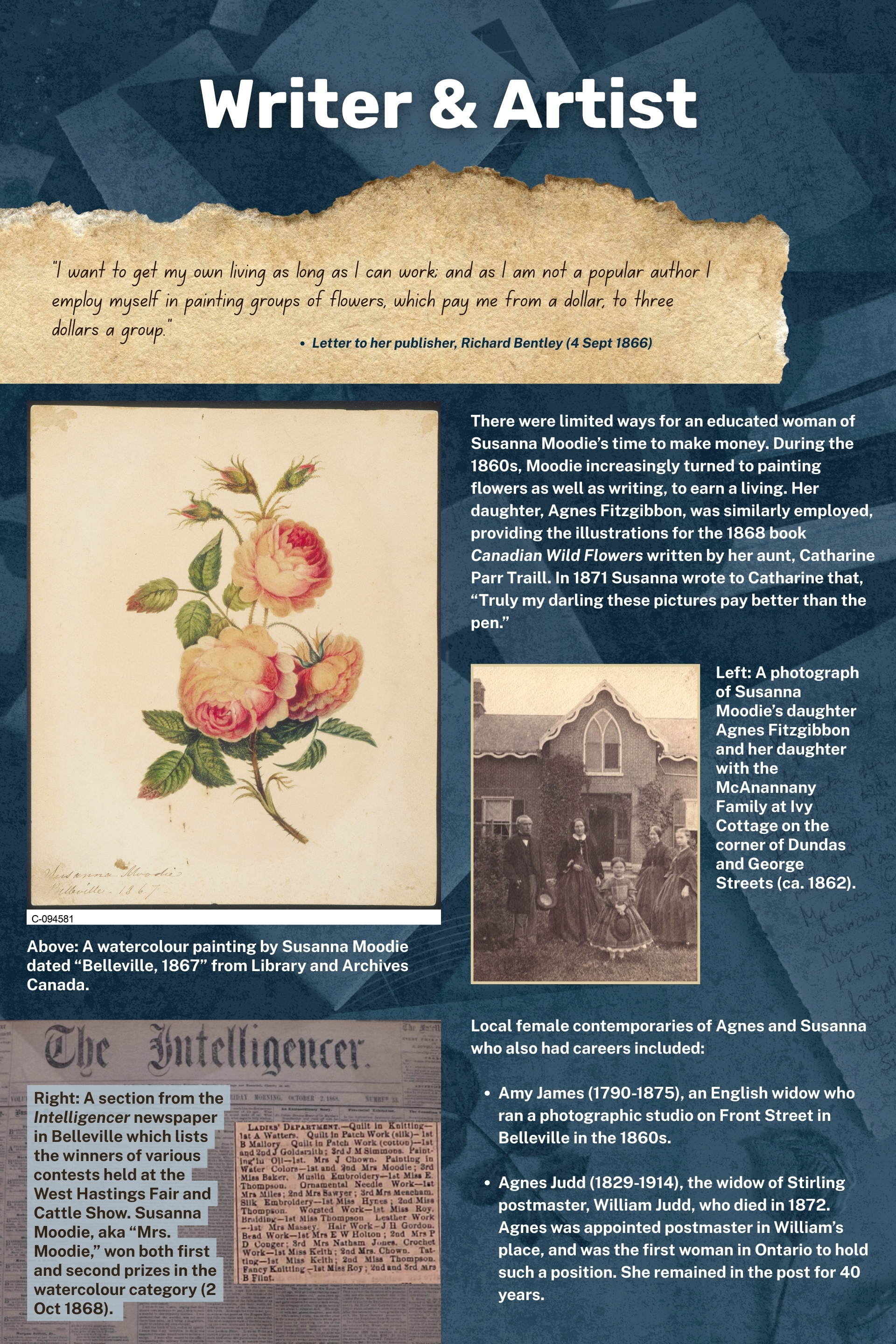

Writer and Artist

There were limited ways for an educated woman of Susanna Moodie’s time to make money. During the 1860s, Moodie increasingly turned to painting flowers as well as writing, to earn a living. Her daughter, Agnes Fitzgibbon, was similarly employed, providing the illustrations for the 1868 book Canadian Wild Flowers written by her aunt, Catharine Parr Traill. In 1871 Susanna wrote to Catharine that, “Truly my darling these pictures pay better than the pen.”

“I want to get my own living as long as I can work; and as I am not a popular author I employ myself in painting groups of flowers, which pay me from a dollar, to three dollars a group.”

- From Letter to her publisher, Richard Bentley (4 Sept 1866)

Local female contemporaries of Agnes and Susanna who also had careers included:

- Amy James (1790-1875), an English widow who ran a photographic studio on Front Street in Belleville in the 1860s.

- Agnes Judd (1829-1914), the widow of Stirling postmaster, William Judd, who died in 1872. Agnes was appointed postmaster in William’s place, and was the first woman in Ontario to hold such a position. She remained in the post for 40 years.

Photographs above include A watercolour painting by Susanna Moodie dated “Belleville, 1867” from Library and Archives Canada; a photograph of Susanna Moodie’s daughter Agnes Fitzgibbon and her daughter with the McAnannany Family at Ivy Cottage on the corner of Dundas and George Streets (ca. 1862); and a section from the Intelligencer newspaper in Belleville which lists the winners of various contests held at the West Hastings Fair and Cattle Show. Susanna Moodie, aka “Mrs. Moodie,” won both first and second prizes in the watercolour category (2 Oct 1868).

The Mighty Moira

“Alas! this river Moira has caused more tears to flow from the eyes of heart-broken parents than any stream of the like size in the province. Heedless of danger, the children will resort to its shores, and play upon the timbers that during the summer months cover its surface… Oh, agony unspeakable! The writer of this lost a fine talented boy of six years…in those cruel waters.”

- From Chapter I, Belleville, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

Deaths of children through disease and accidents were a constant feature in the lives of Moodies and their contemporaries. Susanna herself lost two of her seven children in Belleville. George died less than a month after being born in the summer of 1840. Three years later, six-year-old John drowned in the Moira River while fishing.

Susanna’s own death was registered in Toronto and in Hastings. In the Hastings register page, four of the five other deaths registered alongside hers were of children under five years old:

| Name | Age | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|

| Grover Cleveland Adams | 1 year | Convulsions |

| William Hungerford | 4 years | Scarlet fever |

| Edward Harney | 78 years | Gangrene |

| Walter A. Taugher | 4.5 years | Scarlet fever |

| Margaret G. Taugher | 3 years | Scarlet fever |

The voice of mirth is silenced in my heart,

Thou wert so dearly loved – so fondly cherish’d;

I cannot yet believe that we must part, -

That all, save thine immortal soul, has perish’d –

My boy – my boy!”

- Moodie lamenting the death of her son John, from Chapter I, Belleville, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

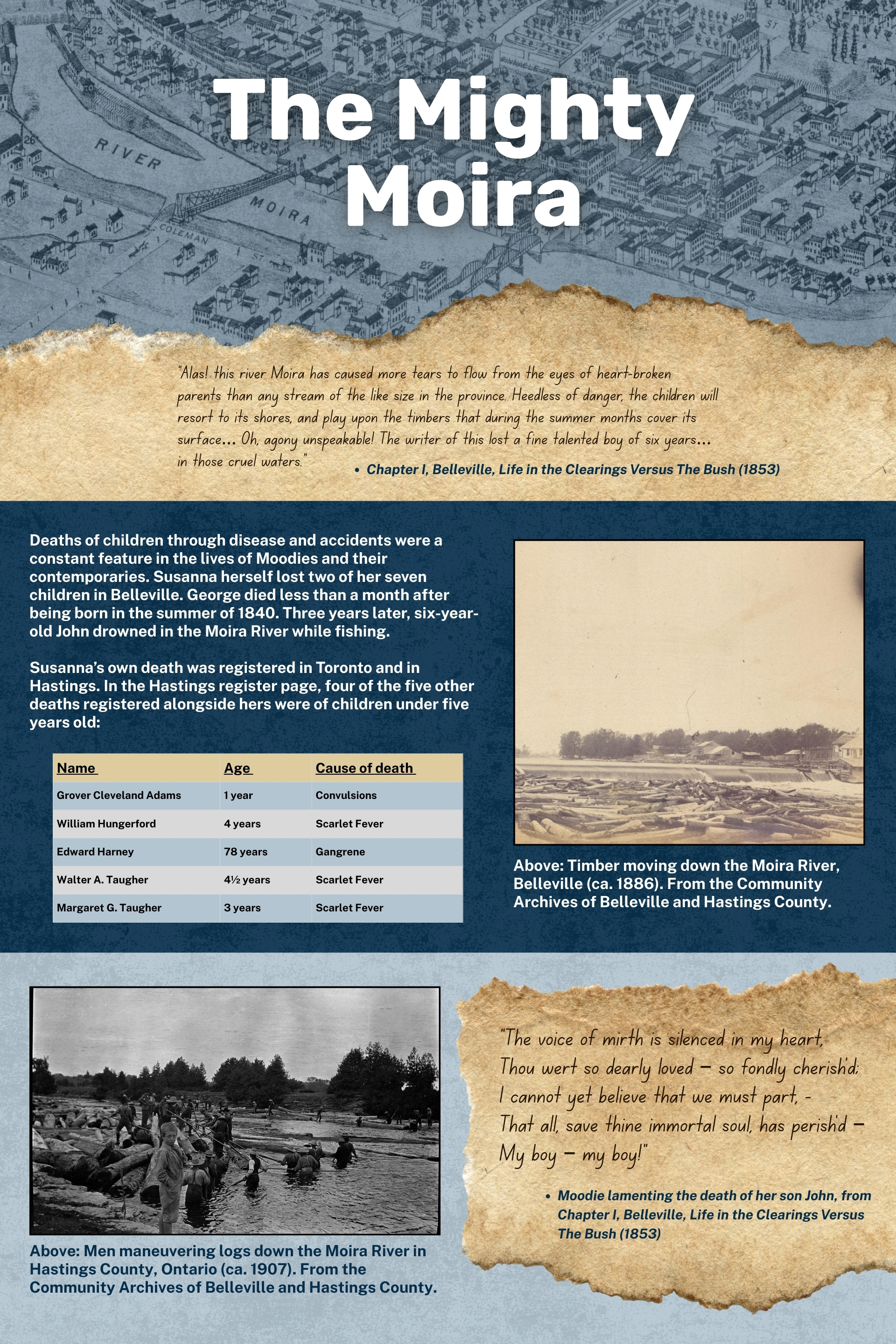

Photographs include timber moving down the Moira River, Belleville (ca. 1886). From the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County; and men maneuvering logs down the Moira River in Hastings County, Ontario (ca. 1907). From the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County.

The Political Pen

The Moodies arrived in Belleville at a time of deep political divisions. Memories of the 1837 rebellion were fresh and local elections often resulted in violence.

John Wedderburn Dunbar Moodie’s appointment as Sheriff of Hastings County caused resentment among people who saw themselves as his political opponents. Susanna Moodie developed a particular dislike of George Benjamin, the owner of the Conservative newspaper, The Intelligencer.

Susanna took her revenge with her pen. In 1843 she created Benjamin Levi, a Jewish newspaper editor, in her story Richard Redpath. Levi was heavily based on George Benjamin.

“The Jew Editor is a true picture drawn from life, which so closely resembles the original that it will be recognized by all who ever knew him, or fell under his lash, a man detested in his day and generation.”

- From a letter to her publisher, Richard Bentley (30 Jan 1854)

Moodie’s vicious caricature of Benjamin did him no political harm, however - in 1856 he became the first Jewish Member of Parliament in Canada, and was a close ally of John A. Macdonald.

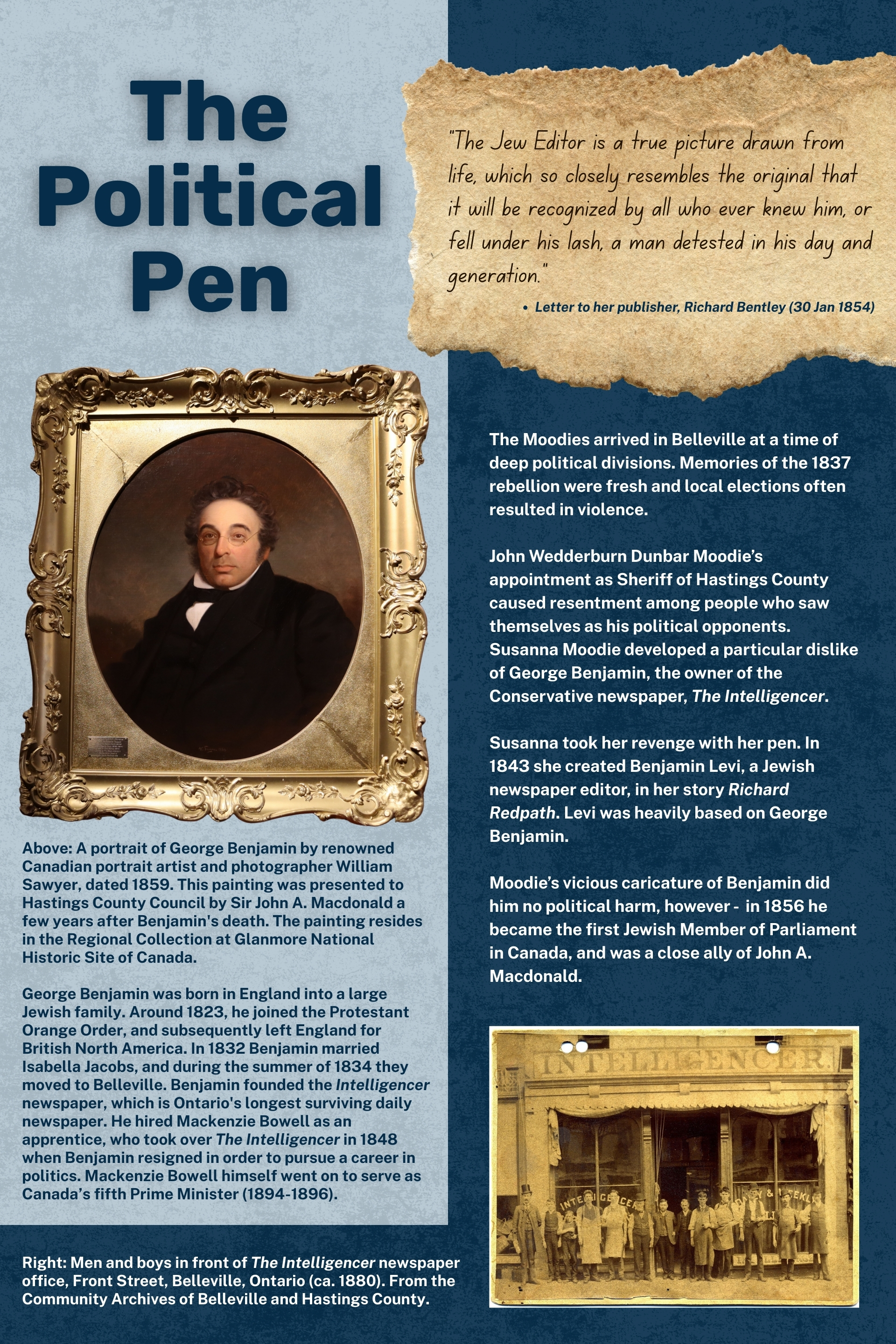

Above: A portrait of George Benjamin by renowned Canadian portrait artist and photographer William Sawyer, dated 1859. This painting was presented to Hastings County Council by Sir John A. Macdonald a few years after Benjamin's death. The painting resides in the Regional Collection at Glanmore National Historic Site of Canada.

George Benjamin was born in England into a large Jewish family. Around 1823, he joined the Protestant Orange Order, and subsequently left England for British North America. In 1832 Benjamin married Isabella Jacobs, and during the summer of 1834 they moved to Belleville. Benjamin founded the Intelligencer newspaper, which is Ontario's longest surviving daily newspaper. He hired Mackenzie Bowell as an apprentice, who took over The Intelligencer in 1848 when Benjamin resigned in order to pursue a career in politics. Mackenzie Bowell himself went on to serve as Canada’s fifth Prime Minister (1894-1896).

Additional photograph included is one of a gathering of men and boys in front of The Intelligencer newspaper office, Front Street, Belleville, Ontario (ca. 1880). From the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County.

Religion and Spiritualism

Susanna Moodie’s writings and letters reveal her complex relationship with Spiritualism, which was on the rise during the early Victorian Era in North America. Moodie’s Protestant upbringing and later religious affiliations emphasized moral duty, providence, and the power of faith during times of hardship. Throughout her writings it is evident that Christianity was a guiding force in navigating the trials of settler life, providing a sense of meaning, purpose, and resilience amid her feelings of isolation and loss during her early years in Canada.

“God forbid that any representations of mine should deter one of my countrymen from making this noble and prosperous colony his future home. But let him leave to the hardy labourer the place assigned to him by Providence, nor undertake, upon limited means, the task of pioneer in the great wilderness.”

- Introduction, Life in the Clearings Versus The Bush (1853)

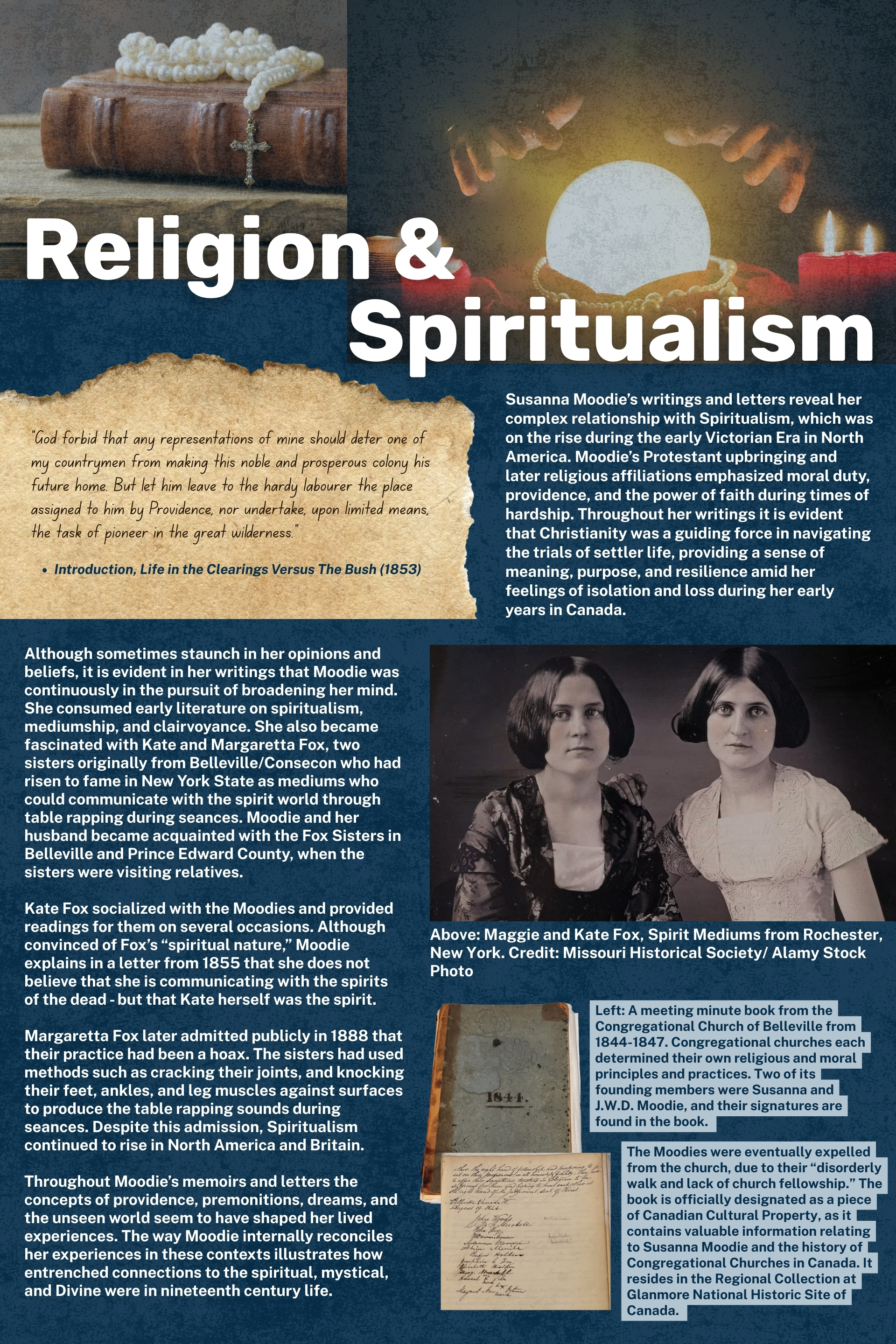

Although sometimes staunch in her opinions and beliefs, it is evident in her writings that Moodie was continuously in the pursuit of broadening her mind. She consumed early literature on spiritualism, mediumship, and clairvoyance. She also became fascinated with Kate and Margaretta Fox, two sisters originally from Belleville/Consecon who had risen to fame in New York State as mediums who could communicate with the spirit world through table rapping during seances. Moodie and her husband became acquainted with the Fox Sisters in Belleville and Prince Edward County, when the sisters were visiting relatives.

Kate Fox socialized with the Moodies and provided readings for them on several occasions. Although convinced of Fox’s “spiritual nature,” Moodie explains in a letter from 1855 that she does not believe that she is communicating with the spirits of the dead - but that Kate herself was the spirit.

Margaretta Fox later admitted publicly in 1888 that their practice had been a hoax. The sisters had used methods such as cracking their joints, and knocking their feet, ankles, and leg muscles against surfaces to produce the table rapping sounds during seances. Despite this admission, Spiritualism continued to rise in North America and Britain.

Throughout Moodie’s memoirs and letters the concepts of providence, premonitions, dreams, and the unseen world seem to have shaped her lived experiences. The way Moodie internally reconciles her experiences in these contexts illustrates how entrenched connections to the spiritual, mystical, and Divine were in nineteenth century life.

Photographs include Maggie and Kate Fox, Spirit Mediums from Rochester, New York. Credit: Missouri Historical Society/ Alamy Stock Photo; and a meeting minute book from the Congregational Church of Belleville from 1844-1847. Congregational churches each determined their own religious and moral principles and practices. Two of its founding members were Susanna and J.W.D. Moodie, and their signatures are found in the book. The Moodies were eventually expelled from the church, due to their “disorderly walk and lack of church fellowship.” The book is officially designated as a piece of Canadian Cultural Property, as it contains valuable information relating to Susanna Moodie and the history of Congregational Churches in Canada. It resides in the Regional Collection at Glanmore National Historic Site of Canada.